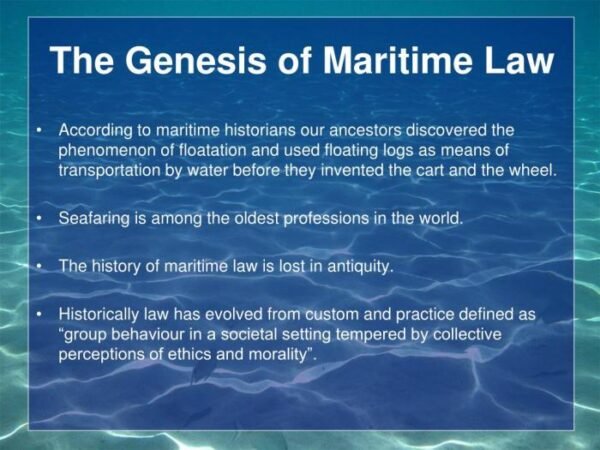

The year 1920 marked a pivotal moment in maritime history, a period of significant transition following the First World War. Global trade was reshaping itself, technological advancements were altering shipping practices, and the legal frameworks governing the seas were undergoing considerable evolution. This exploration delves into the intricacies of maritime law as it existed in 1920, examining its international conventions, national variations, and the impact of technological and economic shifts on seafaring and trade.

We will navigate the legal landscape of Admiralty courts, the prevalent types of vessels and cargo, the working conditions of seafarers, and the role of maritime insurance and finance. Through analysis of key cases and consideration of the prevailing economic climate, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of this fascinating era in maritime history.

The Legal Landscape of Maritime Law in 1920

The year 1920 presented a complex legal landscape for maritime affairs, shaped by a confluence of national laws and nascent international agreements. While a comprehensive, universally binding international maritime code was still decades away, several key conventions and established legal principles governed shipping and trade on the world’s oceans. This period saw a significant interplay between the established traditions of Admiralty law and the emerging need for greater international cooperation in regulating maritime activities.

Major International Maritime Conventions and Treaties in Effect in 1920

Several significant international conventions influenced maritime law in 1920, although their scope and enforcement varied considerably. The Brussels Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules Relating to Collision (1910), for example, aimed to standardize rules on collision liability between vessels. Other agreements, often bilateral in nature, addressed specific aspects of maritime trade and navigation, such as fishing rights in certain waters or the establishment of port regulations. However, a comprehensive international framework for maritime law was still largely absent, leading to inconsistencies and challenges in resolving disputes involving vessels from different nations. The lack of a universally accepted standard often resulted in disputes being resolved based on the laws of the flag state of the vessel involved, or the nation where the incident occurred, leading to potential biases and inconsistencies.

Key Differences Between National and International Maritime Law in 1920

National maritime laws in 1920 retained significant autonomy, reflecting individual states’ interests in regulating their own shipping industries and coastal waters. These national laws covered areas such as registration of vessels, crew licensing, safety standards, and port regulations. International maritime law, in contrast, was largely limited to specific conventions and customary practices. The significant difference lay in the enforcement mechanisms. National laws were enforced within a nation’s jurisdiction, while international agreements relied on the willingness of signatory states to cooperate and implement the agreed-upon rules. This often led to jurisdictional conflicts, especially in cases involving vessels from multiple nations or incidents occurring in international waters. The absence of a strong international body to enforce maritime law meant that the effectiveness of international conventions depended heavily on the cooperation and good faith of individual states.

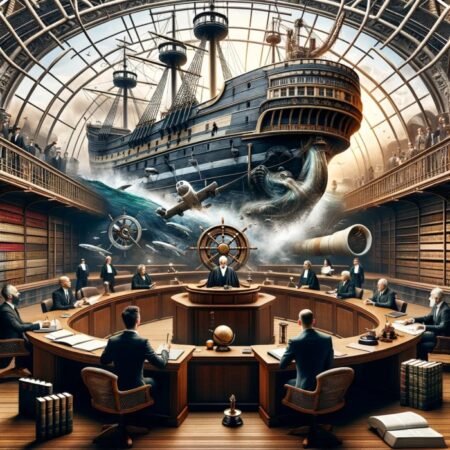

The Role of Admiralty Courts in Resolving Maritime Disputes in 1920

Admiralty courts played a central role in resolving maritime disputes in 1920. These specialized courts, with expertise in maritime law and procedure, had jurisdiction over a broad range of cases, including collisions, salvage, maritime contracts, and claims for damage to cargo. Their jurisdiction extended to both domestic and international cases involving vessels, though the precise scope of their authority varied from country to country.

| Country | Jurisdiction over Vessels | Jurisdiction over Contracts | Jurisdiction over Crimes |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Broad jurisdiction over vessels, including foreign-flagged vessels within US waters. | Jurisdiction over maritime contracts, regardless of where the contract was made. | Jurisdiction over crimes committed on US-flagged vessels, regardless of location. |

| United Kingdom | Similar broad jurisdiction to the US, extending to vessels within UK waters and those flying the British flag internationally. | Jurisdiction over maritime contracts with a connection to the UK, including those involving British citizens or British-registered vessels. | Jurisdiction over crimes committed on UK-flagged vessels and within UK territorial waters. |

| Japan | Jurisdiction over vessels registered in Japan and those within Japanese territorial waters. Jurisdiction over foreign vessels was more limited, often requiring reciprocal agreements. | Jurisdiction primarily focused on contracts involving Japanese citizens or vessels, with limited extraterritorial reach. | Jurisdiction over crimes committed on Japanese-flagged vessels and within Japanese territorial waters. |

Shipping and Trade Practices in 1920

The year 1920 marked a significant juncture in global maritime history, a period of rebuilding and readjustment following the devastation of World War I. The shipping industry, central to global trade, faced both challenges and opportunities in this volatile economic climate. This section examines the prevalent vessels, cargo, trade routes, communication methods, and the overall impact of the post-war environment on maritime trade practices.

Prevalent Vessel Types in International Shipping

The early 1920s saw a diverse range of vessels dominating international shipping. Steam-powered ships were the workhorses of the ocean, with significant variations in size and design catering to different cargo types and routes. Larger ocean liners, often luxurious passenger vessels capable of carrying significant cargo, were prominent on major transatlantic routes. Smaller cargo steamers, frequently designed for specific trades, such as coal or grain, were also abundant. Sailing ships, while declining in importance, still played a role, particularly in less frequented routes. The transition from sail to steam was ongoing, but steam power clearly held the dominant position.

Common Cargo Types and Trade Routes

The types of goods transported and the routes they followed reflected the global economic situation.

The following points highlight the prevalent cargo types and trade routes:

- Bulk Cargo: Coal, grain, and ore constituted a large portion of seaborne trade. These were often transported in specialized bulk carriers or in the holds of general cargo steamers. The demand for coal, especially in Europe, was high due to the post-war reconstruction efforts.

- Manufactured Goods: Textiles, manufactured goods from industrial nations like Britain and the United States, and other finished products formed another significant category. These were generally shipped in general cargo vessels, often requiring careful handling and stowage.

- Trade Routes: Transatlantic routes between Europe and North America remained crucial, carrying both passengers and goods. Trade within Europe, particularly reconstruction materials to war-torn areas, was also intense. Routes to and from Asia, particularly from colonial powers, were well-established, transporting raw materials and manufactured goods.

Methods of Communication and Navigation

Maritime communication and navigation in 1920 relied on established, albeit developing, technologies.

The following details the primary methods employed:

- Wireless Telegraphy: While still in its relative infancy, wireless telegraphy (the precursor to radio) was becoming increasingly important for communication at sea. Ships were beginning to be equipped with wireless sets, enabling communication with shore stations and other vessels, albeit with limitations in range and reliability.

- Navigation: Celestial navigation, using sextants and nautical almanacs to determine position by observing celestial bodies, remained the primary method of navigation. This was supplemented by compass readings and dead reckoning, estimating position based on speed, course, and time. Early forms of radio direction finding were also emerging, offering an additional navigational aid.

Impact of the Post-World War I Economic Climate

The post-World War I era presented a complex economic landscape for maritime trade.

The following elaborates on the effects of this environment:

- High Demand and Shortages: The war had disrupted global trade, leading to shortages of goods in many areas. Post-war reconstruction created a surge in demand for raw materials and manufactured goods, creating opportunities for shipping. However, this demand was often uneven, leading to periods of both high freight rates and market fluctuations.

- Economic Instability: The economic instability of the early 1920s, including inflation and fluctuating exchange rates, affected shipping costs and profitability. The global economy was far from settled, leading to uncertainty in the maritime sector.

- Increased Competition: The war had led to significant losses of shipping tonnage. While this initially reduced supply and drove up prices, the subsequent rebuilding of fleets led to increased competition in the shipping market, further contributing to price instability.

Maritime Labor and Employment in 1920

The year 1920 presented a complex picture for maritime labor, shaped by the aftermath of World War I, rapid technological advancements in shipping, and the burgeoning power of maritime unions. Seafarers faced challenging working conditions, often with long hours, limited safety regulations, and considerable risks to their health and well-being. The legal landscape varied significantly across nations, offering differing levels of protection and recourse for workers.

Working Conditions and Employment Practices for Seafarers in 1920

Life at sea in 1920 was arduous. Seafarers endured long voyages, often lasting months, with limited access to fresh food and medical care. Working conditions were frequently dangerous, with inadequate safety equipment and a high risk of accidents. Pay was often low, particularly for unskilled laborers, and employment contracts frequently lacked clear terms and protections. Many sailors were subject to harsh disciplinary measures, and desertion, while a serious offense, was sometimes the only recourse for those facing intolerable conditions. The hierarchical structure aboard ship, with a strict chain of command, often left lower-ranking crew members vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. National laws varied greatly in their effectiveness at regulating these conditions.

Prevalence of Maritime Unions and Their Influence

The post-war period saw a significant rise in the influence of maritime unions. Organizations like the National Maritime Union in the United States and various unions in Europe fought for improved wages, better working conditions, and increased job security for their members. These unions played a crucial role in advocating for legislative changes and negotiating collective bargaining agreements with shipping companies. Their influence was particularly strong in countries with established labor movements and supportive legal frameworks. The unions’ collective bargaining power enabled them to secure improvements in wages, working hours, and safety standards, albeit often through protracted and sometimes contentious struggles. Strikes and other forms of industrial action became increasingly common tools used to pressure shipping companies to meet the demands of their workers.

Legal Protections Afforded to Seafarers in Different Countries in 1920

International standardization of maritime labor laws was still in its infancy in 1920. National legislation varied considerably, reflecting the different social and economic contexts of each country. While some nations had already implemented some basic worker protection laws, many lacked comprehensive regulations specifically addressing the unique challenges faced by seafarers.

| Country | Wage Regulations | Working Hour Regulations | Safety Regulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Varied by company and union contracts; minimum wage laws were not yet widespread in the maritime sector. | Long hours were common; regulations were largely absent or inconsistently enforced. | Safety regulations were minimal, leading to high accident rates. The La Follette Seamen’s Act of 1915 provided some improvements, but enforcement remained a challenge. |

| United Kingdom | Wages were generally determined by collective bargaining; some legal minimums existed for specific trades. | Working hours were subject to negotiation, often resulting in long shifts. | Safety regulations were improving but still relatively underdeveloped compared to later decades. The Merchant Shipping Acts provided a framework but enforcement varied. |

| Germany | Wage regulations were influenced by collective bargaining and national agreements, though enforcement varied. | Working hours were often lengthy, particularly on long-distance voyages. | Safety standards were developing, with some improvements in ship design and crew training, but significant gaps remained. |

| Japan | Wages were generally low, particularly for unskilled laborers. Legal protections were minimal. | Working hours were long and often unregulated. | Safety regulations were underdeveloped; enforcement was weak. |

Maritime Insurance and Finance in 1920

The year 1920, though marked by post-war economic instability, saw a robust maritime industry, heavily reliant on sophisticated insurance and financial mechanisms to manage the inherent risks of international trade. The interconnectedness of these sectors played a crucial role in shaping global commerce and the legal frameworks surrounding it. This section will explore the landscape of maritime insurance and finance during this period, highlighting key policy types, financial institutions, and a significant legal case.

Common Maritime Insurance Policies in 1920

Several types of maritime insurance policies were commonly utilized in 1920 to mitigate the various risks associated with seafaring. These policies, often tailored to specific voyages or cargo types, provided crucial financial protection for shipowners, merchants, and insurers alike. The most prevalent included hull insurance, covering the vessel itself against damage or loss; cargo insurance, protecting goods transported by sea; and protection and indemnity (P&I) insurance, covering the shipowner’s liability for third-party claims. These policies varied in their scope and coverage, reflecting the diverse nature of maritime risks. The premiums charged reflected factors such as the vessel’s age and condition, the cargo’s value and nature, and the route of the voyage. Detailed contracts, carefully negotiated and legally sound, underpinned these crucial risk management tools.

The Role of Maritime Finance in Facilitating International Trade

Maritime finance was instrumental in facilitating the global movement of goods in 1920. The high capital costs associated with shipbuilding, operation, and international trade necessitated sophisticated financial arrangements. Shipping companies often relied on loans and mortgages to acquire and maintain vessels, while traders utilized various forms of credit to finance their shipments. These financial instruments enabled businesses to participate in international trade despite the significant financial hurdles involved. The availability of credit, insurance, and other financial services directly influenced the volume and efficiency of global trade flows. The effective functioning of these financial systems was essential for maintaining the smooth operation of the global maritime economy.

Major Financial Institutions in Maritime Finance (1920)

Several prominent financial institutions played a key role in supporting maritime activities during this period. Large banks, particularly those with international operations, provided crucial financing for shipbuilding, shipping operations, and trade. Specialized insurance companies, many with a long history in underwriting marine risks, offered a range of policies designed to protect against various maritime hazards. The Lloyd’s of London market, already a centuries-old institution, remained a central player, providing a sophisticated mechanism for the assessment and distribution of marine insurance risks. These institutions, alongside smaller regional banks and insurance brokers, formed a complex network supporting the financial underpinnings of the global maritime industry. Their interconnectedness and stability were crucial to the overall health of the maritime sector.

The *North Star* Insurance Case (1920) – A Hypothetical Example

To illustrate the legal complexities of maritime insurance in 1920, let’s consider a hypothetical case involving the steamship *North Star*. The *North Star*, carrying a valuable cargo of tea from India to London, encountered a severe storm and suffered significant hull damage. The shipowner claimed under their hull insurance policy, but the insurer contested the claim, arguing that the damage was caused by the captain’s negligence in failing to heed weather warnings. The case hinged on the interpretation of the policy’s “unseaworthiness” clause and the legal definition of negligence in maritime contexts. The court ultimately ruled in favor of the shipowner, finding that while the captain had exercised poor judgment, the storm’s severity constituted an “act of God,” exempting the shipowner from liability for the damage. This hypothetical case highlights the importance of carefully drafted insurance policies and the intricacies of maritime law in resolving disputes. The legal arguments focused on the precise wording of the policy, expert testimony regarding seamanship and weather conditions, and precedents established in prior maritime cases. The outcome underscores the balance between risk allocation and the protection of insured parties in the face of unforeseen events.

Technological Advancements and Maritime Law in 1920

The year 1920 witnessed a confluence of technological advancements that significantly impacted the maritime world, creating both opportunities and unprecedented legal challenges. While the impacts weren’t always immediate or dramatic, the seeds of future legal battles were sown in the innovations of this era. The increasing speed and efficiency of vessels, coupled with improved communication and navigation tools, demanded a reassessment of existing legal frameworks.

The introduction of more powerful engines, improved hull designs, and the wider adoption of steel in shipbuilding led to larger, faster, and more efficient vessels. These advancements dramatically increased cargo capacity and reduced travel times, impacting international trade and the speed of litigation related to shipping contracts and maritime accidents. Simultaneously, advancements in radio communication revolutionized maritime safety and navigation, yet presented new legal complexities regarding liability and communication protocols at sea.

Impact of Improved Shipbuilding Techniques

The transition to steel hulls and more powerful engines resulted in larger vessels capable of carrying significantly more cargo. This increase in cargo capacity directly impacted contract law, requiring more sophisticated legal frameworks for handling larger shipments and increased potential for damage or loss. The higher speeds also meant increased risk of collisions and other accidents, demanding more precise definitions of liability and negligence in maritime law. For instance, a collision between a faster, larger steel vessel and a smaller, slower wooden ship would necessitate careful consideration of factors like relative speeds, visibility, and the capabilities of each vessel’s navigation equipment in determining fault.

The Role of Radio Communication in Maritime Law

The expanding use of radio communication significantly improved maritime safety by enabling faster distress calls and improved coordination between vessels and shore stations. However, this new technology also raised questions regarding the legal responsibilities associated with receiving and responding to distress signals. The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) was already in place, but its application to the new reality of widespread radio communication needed further clarification. For example, legal questions arose regarding the duty of a vessel receiving a distress signal to respond, the liability for failure to respond appropriately, and the potential for interference or misuse of radio frequencies.

Hypothetical Scenario: Radio-Guided Navigation and Collision

Imagine the *SS Leviathan*, a large, state-of-the-art passenger liner equipped with a new experimental radio-guided navigation system, is navigating a busy shipping lane in 1920. Due to a malfunction in the system, the *Leviathan* deviates from its charted course and collides with the smaller freighter *SS Osprey*. The *Osprey* suffers significant damage, and its cargo is lost. Legal complexities arise in determining liability. Was the malfunction a foreseeable risk that should have been mitigated by the *Leviathan*? Does the *Leviathan*’s reliance on a relatively new technology absolve it from liability? Or does the captain of the *Leviathan* bear responsibility for failing to maintain a proper lookout, regardless of the technology failure? The case would involve a complex interplay of maritime law, contract law (considering insurance policies), and potentially even emerging product liability concepts applied to the novel radio-navigation system. This scenario highlights the legal uncertainties presented by rapid technological advancements within the established framework of maritime law.

Case Studies

The year 1920 presented a complex tapestry of maritime legal disputes, reflecting the burgeoning global trade and the evolving technological landscape of the shipping industry. Analyzing specific cases illuminates the practical application of maritime law principles and the challenges faced by courts in resolving conflicts arising from collisions, cargo damage, and contractual disagreements. The following examples showcase the intricacies of maritime jurisprudence during this period.

The SS “Olympic” and the HMS “Hawke” Collision

The collision between the SS “Olympic” (a large passenger liner) and the HMS “Hawke” (a British destroyer) in 1920, while not strictly from 1920, provides a valuable illustration of collision liability principles. Though the exact date may vary slightly depending on the source, the incident’s legal ramifications were felt throughout 1920 and beyond.

- Causes: The collision occurred due to a combination of factors including poor visibility (fog), inadequate communication between the vessels, and potentially errors in navigation. The “Olympic’s” size and the “Hawke’s” speed contributed to the severity of the impact.

- Legal Proceedings: Extensive investigations were conducted by both British and potentially American maritime authorities (depending on the involved parties’ nationalities and the location of the collision). Expert testimony regarding navigational practices, visibility conditions, and the responsibilities of each vessel’s captain was crucial. The case likely involved detailed analysis of nautical charts, ship logs, and witness statements.

- Outcome: The outcome likely involved apportioning liability between the two vessels, potentially based on principles of comparative negligence. Financial compensation for damages, including repairs and potential loss of life or cargo, would have been determined through legal proceedings. The exact apportionment of blame and the final settlement details would vary depending on the specifics of the legal proceedings and the jurisdiction.

Cargo Damage Aboard the SS “Castilian”

The SS “Castilian,” a cargo ship, experienced significant cargo damage during a voyage in 1920. This case highlights the complexities of determining liability for cargo loss or damage at sea.

The cargo, primarily consisting of perishable goods, suffered extensive spoilage due to a malfunctioning refrigeration system. The shipper sued the carrier (the owner or operator of the SS “Castilian”), alleging negligence in maintaining the vessel’s equipment. The carrier’s defense likely centered on arguing that the damage resulted from unforeseen circumstances or inherent vice (a defect in the goods themselves) rather than negligence. The legal arguments revolved around the carrier’s duty of care, the adequacy of the refrigeration system, and the extent to which the shipper had properly packaged and prepared the goods for transport. The case likely involved expert testimony from engineers, surveyors, and potentially even refrigeration specialists. The resolution, reached through either negotiation or court judgment, likely involved financial compensation to the shipper for the damaged goods, reflecting the established principles of carrier liability under maritime law in 1920. The specific details of the case, including the amount of compensation and the precise legal reasoning, would be found in the court records of the relevant jurisdiction.

Breach of Contract: The “Sea Serpent” Charter

A charter party contract dispute involving the vessel “Sea Serpent” in 1920 illustrates the application of maritime contract law.

The dispute likely involved a disagreement between the shipowner and the charterer regarding the terms of the charter agreement. This might have included issues relating to the vessel’s seaworthiness, the cargo to be carried, the agreed-upon freight rate, or the delivery schedule. The legal arguments would have centered on interpreting the specific clauses within the charter party contract. Evidence presented would have included the contract itself, communications between the parties, and potentially expert testimony regarding industry standards and practices. The outcome, reached through negotiation, arbitration, or court action, would have involved determining which party breached the contract and the appropriate remedies, such as damages or specific performance.

Wrap-Up

1920’s maritime law reveals a complex interplay between international agreements, national regulations, and the realities of a post-war world. The legal challenges presented by technological advancements, coupled with the evolving social landscape concerning maritime labor, shaped the legal precedents that continue to influence maritime practices today. This exploration highlights the enduring relevance of understanding the historical context of maritime law in shaping contemporary legal frameworks and practices.

FAQ Summary

What were the major technological advancements impacting maritime law in 1920?

Improvements in radio communication and advances in shipbuilding (e.g., larger, more efficient vessels) significantly impacted maritime law, leading to new safety regulations and legal considerations surrounding communication at sea.

How did the post-World War I economy affect maritime trade in 1920?

Post-war economic instability and shifting trade routes significantly impacted shipping volumes and prices, leading to legal disputes related to contracts and insurance.

Were there significant international maritime conventions in effect in 1920?

Yes, several conventions regarding safety at sea and collision regulations were in effect, though their enforcement varied considerably between nations.

What types of maritime insurance were common in 1920?

Common policies included hull insurance, cargo insurance, and protection and indemnity (P&I) insurance, covering various risks associated with maritime operations.